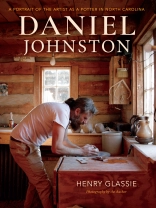

DANIEL JOHNSTON, raised on a farm in Randolph County, returned from Thailand with a new way to make monumental pots. Back home in North Carolina, he built a log shop and a whale of a kiln for wood-firing. Then he set out to create beautiful pots, grand in scale, graceful in form, and burned bright in a blend of ash and salt. With mastery achieved and apprentices to teach, Daniel Johnston turned his brain to massive installations.

First, he made a hundred large jars and lined them along the rough road that runs past his shop and kiln. Next, he arranged curving clusters of big pots inside pine frames, slatted like corn cribs, to separate them from the slick interiors of four fine galleries in succession. Then, in concluding the second phase of his professional career, Daniel Johnston built an open-air installation on the grounds around the North Carolina Museum of Art, where 178 handmade, wood-fired columns march across a slope in a straight line, 350 feet in length, that dips and lifts with the heave while the tops of the pots maintain a level horizon.

In 2000, when he was still Mark Hewitt’s apprentice, Daniel Johnston met Henry Glassie, who has done fieldwork on ceramic traditions in the United States, Brazil, Italy, Turkey, Bangladesh, China, and Japan. Over the years, during a steady stream of intimate interviews, Glassie gathered the understanding that enabled him to compose this portrait of Daniel Johnston, a young artist who makes great pots in the eastern Piedmont of North Carolina.

Table des matières

1. Beginnings

2. Apprenticeship

3. East and West

4. Building a Shop and Making a Pot

5. Firing

6. Selling

7. New Directions

Afterword

Notes

Oral Sources

Bibliography

Index

A propos de l’auteur

HENRY GLASSIE, College Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, has done fieldwork on five continents, written twenty books, and received many awards for his work, including the Chicago Folklore Prize, the Haney Prize in the Social Sciences, the Cummings Award of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the Nigerian Studies Association Book Award, the Outstanding Achievement in the Arts Award from the Assembly of Turkish American Associations, the Friend of Bangladesh Award from the Federation of Bangladeshi Associations, the Lifetime Achievement Award of the American Folklore Society, and the Charles Homer Haskins Prize of the American Council of Learned Societies for a distinguished career of humanistic scholarship. Three of his books — Passing the Time in Ballymenone, The Spirit of Folk Art, and Turkish Traditional Art Today — were named among the notable books of the year by the New York Times.