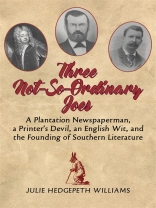

One of the more eccentric figures in the antebellum South was Joseph Addison Turner, born to the plantation and trained to run one. All he really wanted to do, though, was to be a famous writer—and to be the founder of Southern literature. He tried and failed and tried and failed at publishing magazines, poems, books, articles, journals, all while halfheartedly running a plantation. When the Civil War broke out, he no longer had access to New York publishers, and in his frustration it dawned on him that he could throw a newspaper press into an outbuilding on his Georgia plantation. Furthermore, his newspaper would be modeled on The Spectator, the literary newspaper of the early 1700s by Joseph Addison, for whom Turner was named. The Spectator in its day, and 150 years later in Turner’s day, was considered high literature. Turner carefully copied Addison’s style and philosophy—and it worked! His newspaper, The Countryman—the only newspaper ever published on a plantation—was one of the most widely read in the Confederacy. Following Addison’s lead, Turner suggested that slaves should be treated well, lauded the contributions of women, and featured humorous copy. And, of course, his paper celebrated Southern culture and creativity. As Turner urged in The Countryman, the South could never be a great nation if all it did was fight. It needed art—it needed literature! And he, J. A. Turner himself, would lead the way.

The Civil War, however, didn’t go as Turner had hoped. Sherman’s army marched through and took Turner’s world with it. His newspaper collapsed. He died a few years after the war ended, thinking he had failed to start Southern literature.

However, he was wrong. The Countryman’s teenage printer’s devil was Joel Chandler Harris, who grew up to write the first wildly popular Southern literature, the Uncle Remus tales. Turner had taken in the illegitimate, ill-educated Harris and had turned him into a writer. And while Harris worked for the plantation newspaper, he joined Turner’s children at dusk in the slave cabins, listening to the fantastical animal stories the Negroes told. Young Harris recognized the tales’ subversive theme of the downtrodden outwitting the powerful. Years later as a newspaperman, he was asked to write a column in the Negro dialect, and he reached back to his days at The Countryman for the slaves’ narratives. The stories enthralled readers in the South—but also in the North, particularly Theodore Roosevelt. The Uncle Remus stories were hailed as the reconciler between North and South, and they directly influenced Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling, and Beatrix Potter. Most importantly, Uncle Remus knocked New England off its perch as the focus of American belles-lettres and made Southern literature the primary national focus.

So, ultimately, Joseph Addison Turner really did found Southern literature—with the help of two other not-so-ordinary Joes, Joseph Addison and Joel Chandler Harris. Julie Hedgepeth Williams tells their story.

Об авторе

JULIE HEDGEPETH WILLIAMS is an adjunct communication and media professor at Samford University. She is also the recipient of the 2021 Kobre Award for Lifetime Achievement in Journalism History. Williams is the author or coauthor of eleven books, including Wings of Opportunity: The Wright Brothers in Montgomery, Alabama.