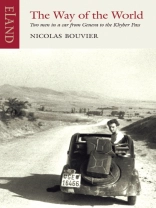

The Way of the World, a cult classic, is the beguiling tale of an impecunious and life-enhancing journey from Geneva to the Khyber Pass in the ’50s. When Nicolas Bouvier and the artist Thierry Vernet set out, they had money for four months and a sturdy Fiat Topolino. They broke their journey when money ran low, to teach and sell paintings and articles in Istanbul, Tabriz and eventually in Quetta. Gravitating towards the poorer neighbourhoods, they spent intoxicating nights listening to gypsy musicians, trading poetry with Iranian tramps and entertaining their fellow drinkers with songs and an accordion. The Way of the World is also a journey towards the self. ‘You think you are making a trip, ‘ writes Bouvier, ‘but soon it is making you – or unmaking you.’

Про автора

Nicolas Bouvier was born in 1929 near Geneva, where he died in 1998. Although he was the greatest Swiss travel writer of the 20th century, he was not a restless character. When he did travel, he liked to take it very slowly, and was proud to note that it had taken him longer to get to Japan than Marco Polo. He loved animals, and particularly admired the donkey, whose patience, endurance and humility reminded him of the quiet competence of the good traveller. The youngest of three children of an enlightened and intellectual family (his father was a librarian), Bouvier’s early reading of RL Stevenson, Jules Verne, Jack London and Fenimore Cooper made him impatient for the world, and he recalls, ‘At eight years old, I traced the course of the kon with my thumbnail in the butter on my toast’. He was encouraged to travel as a teenager by his father, who perhaps sensed that there was no holding his son in the Calvinist, careful, bourgeois Bouvier household. It was during a three-day trek in the Finnish tundra, bivouacking under the stars, that he realised the nomadic state had something to teach him. Without waiting for the result of his degree, in 1953 he left to join Thierry Vernet in goslavia with no intention of returning. The fruits of this companionable journey of a year and a half were published some eight years later, in 1963. Where The Way of the World stops, Bouvier continued, through India to Ceylon and thence to Japan. From his experience of Ceylon in 1955 came The Scorpion-Fish, a novel first published in 1981, and from Japan, where he was to live for more than a year and to revisit in the 1960s and 1970s, came a distillation of experiences, The Japanese Chronicles, which were published in their final version in 1975. It was in Japan, to save himself from starvation, that Bouvier took up photography, and developed an eye for imagery which was to become the second string to his career. He became what he called an iconographer, finding images for authors or editors of books and magazines, for designers and costumiers or advertisers. Thierry Vernet was born in Geneva on 12 February 1927, two years earlier than Nicolas Bouvier. Both came from highly educated families. The son of open-minded parents, Vernet does not seem to have been stifled by the Calvinist environment with the same acuteness as his friend Bouvier, who alludes to it variously in his essays – is not Geneva sometimes referred to as the protestant Rome? Tolerance for different peoples was a part of who Thierry was: ‘A generous guy, incapable of hatred’ the Swiss gallery owner Richard Aeschlimann who encouraged his career recalls, adding ‘but he knew how to fend for himself ‘. During Vernet’s adventurous journey with Bouvier, while they were sharing costs, Thierry was feeding the common till selling drawings made while travelling. In his introduction to Thierry’s exhibition organized in 1954 by the Franco-Iranian Institute in Tehran, Bouvier wrote: ‘I watch him work, instinctively neglecting superficial values in favour of Nature and Earth, and especially the fellow men he finds in nooks and crannies along the way.’ Thierry’s drawings were full of talent, intelligence, tenderness and humour. Though a free man, Vernet was no Bohemian, but rather an elegant, blond and delicate gentleman. And because God, despite His reputation, is not fair, He also bestowed on him multiple talents, among them the gift of music, as well as painting. In his luggage, Vernet carried his seasoned accordion: tool of genuine delight in joining improvisations of gypsy orchestras encountered on dusty roads. Years went by. In 1958 Vernet settled in Paris with his wife Floristella, also a painter, with whom he shared a rare love. Music remained important in his life, but this time it was at the organ of the protestant church in Belleville, where he spent long hours playing. Thierry Vernet died on 1 October 1993 in the Rothschild hospital in Paris after several chemotherapy treatments.